The zoo’s planned development onto Knowland Park habitat currently used by multiple wild animals will include exhibits featuring captive animals that no longer are native to the area–due to loss of habitat and other human activities. It will also include exhibits displaying captive specimens of animals that are still around here in the wild and currently using Knowland Park for hunting, raising their young, and migration between habitat zones. The irony of this seems so obvious that it is sometimes hard for environmentally active folks to understand how zoo patrons can possibly support such a destructive project. One explanation may lie in the fact that zoo animals become personal to people, particularly those who visit often: they are given names like Molly, Milou, Ginger and Grace, the tigers rescued last year from a private zoo in Texas, and people begin the process of identifying with them.

This process, which often includes attributing human characteristics to the animals, may inspire more empathy for the captives. It renders once-wild animals “tamed” to the ticket-buying public. They become members of the family, and zoos often cultivate that feeling among their patrons. But wild creatures, argue many environmentalists and deep ecologists, are not and should not be tamed. It is, in fact, when wild animals become partially used to human beings that they are most at risk and most potentially destructive—witness the human-bear encounters of recent years that have ended in bears’ deaths. We ought to feel a little chill of fear at the thought of wild animals—and yet, if we leave them alone, and leave them space enough, they generally do the same for us.

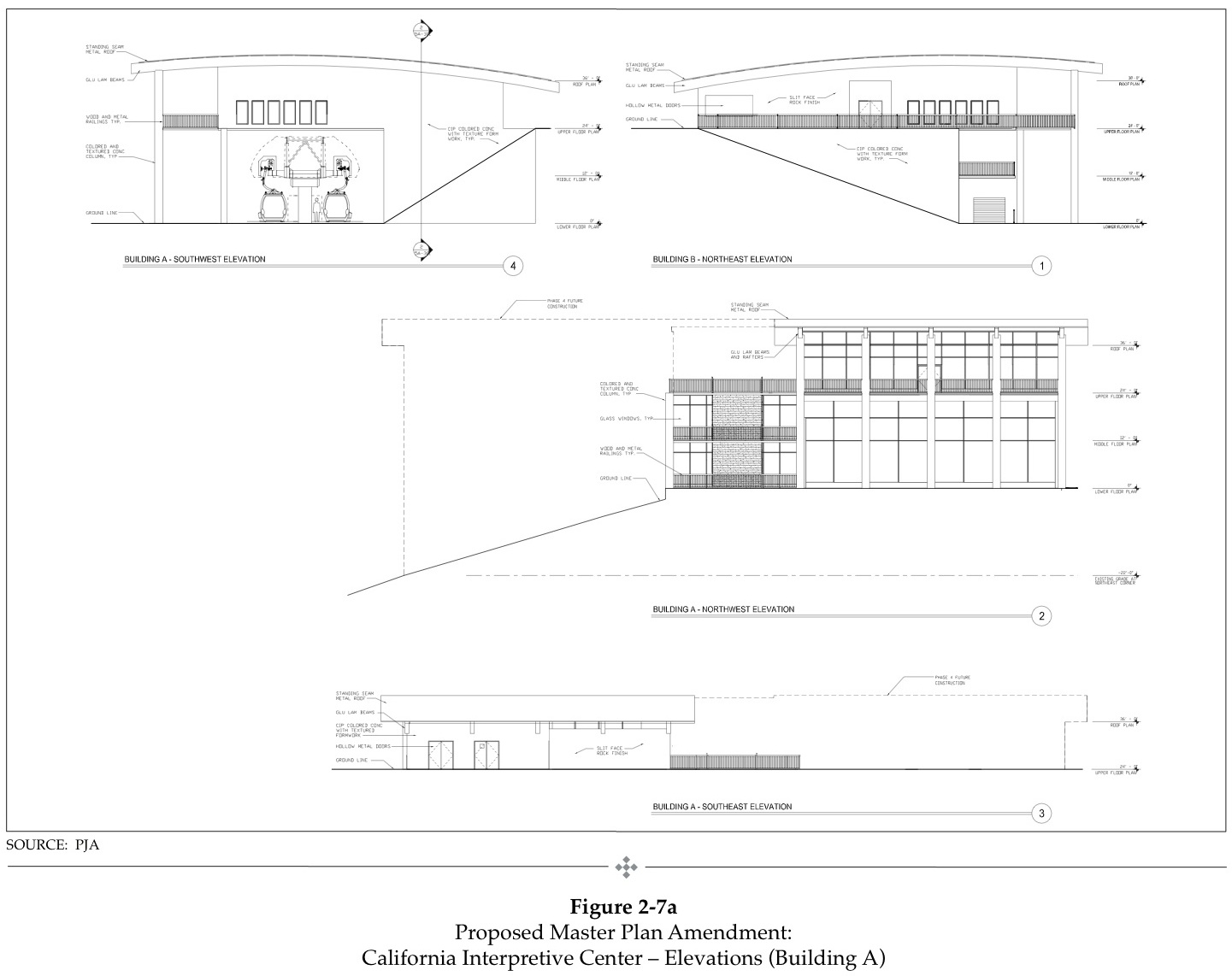

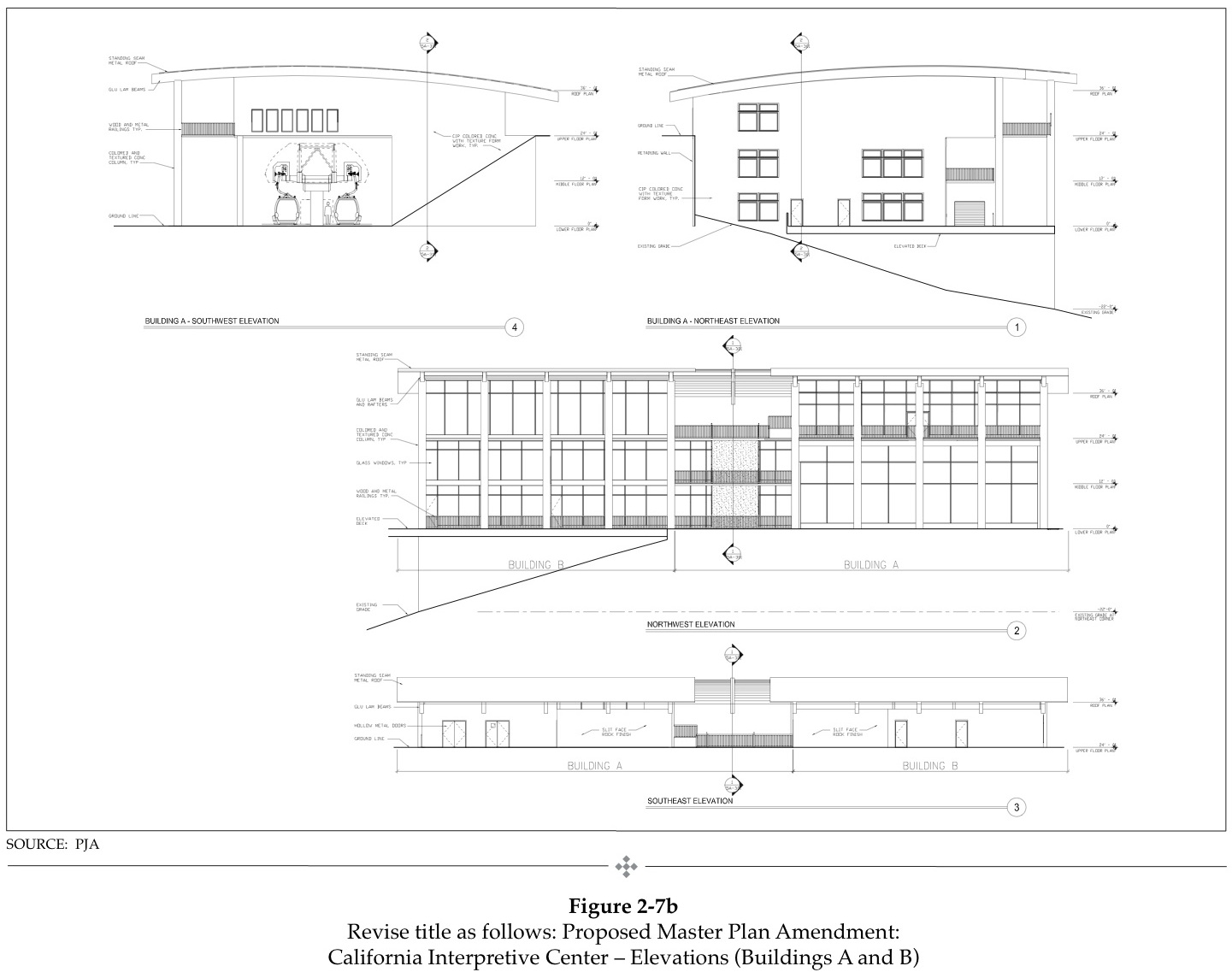

The single largest contributor to loss of species biodiversity is loss of habitat. That is as true in the Bay Area as it is in exotic places. Yet the zoo’s planned 34000 square foot interpretive center building and aerial gondola, positioned atop an area where mountain lions and bobcats now hunt, will displace them from their native food sources and reduce their available range. They will be forced to abandon their ancestral land or die, unnoticed and unmourned by the crowds of people who will never know their names because they haven’t any.

The original plan for this development said the visitor center would be sited on already disturbed land, which would have preserved the habitat. Not any more. That 3 story building will, in a real way, stand forever as a Tomb of the Unknown Bobcat and Mountain Lion—adjacent to the exhibit of a captive mountain lion (bearing an appealing human name) acquired from somewhere else.

It doesn’t have to be this way. As human beings, we can learn from our past mistakes. We can—and must–do better by the creatures who share this land with us. The zoo ought to walk the talk and practice true conservation in its own back yard.

Ruth Malone is a resident of Oakland since 1983, a founding member and co-chair of Friends of Knowland Park and a longtime Oakland neighborhood activist. Since 2007, she has been working to educate and organize environmentalists, park users, and community members to protect the park. In her day job, she is a professor of nursing and health policy at University of California, San Francisco, where she helps students study the links between health and political, social and natural environments, and conducts research on the tobacco industry and its efforts to thwart public health efforts worldwide.

Ruth Malone is a resident of Oakland since 1983, a founding member and co-chair of Friends of Knowland Park and a longtime Oakland neighborhood activist. Since 2007, she has been working to educate and organize environmentalists, park users, and community members to protect the park. In her day job, she is a professor of nursing and health policy at University of California, San Francisco, where she helps students study the links between health and political, social and natural environments, and conducts research on the tobacco industry and its efforts to thwart public health efforts worldwide.

Ruth Malone’s Reflections Blog offers a combination of reflective essays and updates from the Protect Knowland Park Campaign, linking the fight to protect Knowland Park to broader environmental and ethical issues.

Follow

Follow

Comments are closed.